The "First Secret" Problem

Trust is an important property. Actually, it is the single most important property of them all. With trust we can bootstrap security, as security cannot be fabricated out of thin air. However, trust has an inherited problem, it requires you to assume that something is true, verified, confidential, integral or, simply, secure.

This is why, as a rule of thumb, a system, to be secure, should be built so that it doesn’t make many trust assumptions.

A very good example of such trust issue is the so-called “first secret problem”. There is not a formal definition of the “first secret problem” but we could refer to it as the problem of bootstrapping a system which requires some confidential information (e.g., a password or an authentication token) in order to work. Imagine you have a bash script that runs as a cron job and queries an API using an authentication token. The authentication token is our secret and we need the script to use it. The problems that you might have to face when handling such secret are:

- Creation: how do we create the secret?

- Storage: where do we store the secret?

- Consumption: how does our system access the secret?

I’ve seen many times the suggestion of having the secret stored in an encrypted file so that the cron job can read it from there. Let’s see what would happen in that case:

- Creation: we are going to manually create the secret and encrypt it with a password. We should be careful to not issuing commands that expose our secret within the shell history.

- Storage: the secret is encrypted and thus protected in case of un-authorised access to the device storing it.

- Consumption: our shell script can read the encrypted file, but it needs a password in order to decrypt the content of the file, so we are back at square one. Moreover, the level of confidentiality of this other password is no different from the level of confidentiality of the token it protects.

This is, in a nutshell, the first secret problem.

How do we solve it? Unfortunately, we cannot solve it with a definite solution that would work in all situations, there’s no “one size fits all” solution (otherwise we would probably be able to fabricate security out of thin air).

In the remainder of this post I will describe a scenario and I shall attempt at describing a number of solutions that could be used to solve the “first secret problem”. Note that I will most likely not provide an exhaustive list of solutions but rather a general overview of the most common ones (or at least the ones that popped into my brain).

Scenario

Let’s describe a simple scenario and the attacker we want to protect ourselves from.

You have a standalone application running that takes a backup of a folder and stores the backup on a network folder that is already mounted on the system. The backup you want to take is encrypted and therefore the backup application requires a password. In this example, the “first secret problem” is the password used to encrypt the backup.

As for the attacker, say you want to protect from a remote attacker that might want to attempt at compromising the machine where the backup script is running, e.i. the attacker does not have physical access to the machine itself.

How shall we handle it?

However, before getting into the juice part, allow me to make a quick remark: please, please, please 🙏, before picking up a solution (any solution) to any security issue, make sure you fully understand the problem you are trying to solve, the attack scenario you want to prevent and you want to achieve. Do not pick the most complicated solution just because it’s considered to be the “safest one”. You might end up implementing an incredible complicated mechanism to solve a problem you probably didn’t even have.

Command parameter

Imagine the case where the password is passed to the application via command line parameter.

- Creation: passing it in the prompt as parameter.

- Storage: none, the secret is stored only in memory while the backup application runs.

- Consumption: the application reads the secret from the prompt parameters.

Security consideration for creation: - The secret is displayed on screen, which will most likely always be the case, and not so much a problem if you are alone in the room.

- The secret gets saved in the history of the shell, a problem in case other people have access to the same account on the same machine.

Security consideration for storage: - The secret does not get permanently stored.

Security consideration for feeding: - The secret is directly read as a parameter which makes it safe enough from a confidentiality or integrity point of view.

Environment Variables

Imagine the case where the password is feed to the application via environment variables.

- Creation: a shell commands issued by the user to create an environment variable;

- Storage: environment variable;

- Consumption: the application reads the environment variable.

Security consideration for creation: - The secret is displayed on screen (again), which will most likely always be the case, and not so much a problem if you are alone in the room.

- The secret gets saved in the history of the shell since it is created via shell commands. This can be a problem in case other people have access to the same account on the same machine.

Security consideration for storage: - The secret is stored in the environment variable. Generally speaking, an attacker that has access to the environment variables is already an attacker that has a pretty important foothold in the entire system and thus, you might have bigger problems.

Security consideration for feeding: - The secret is directly read from the environment variable which makes it safe enough from a confidentiality or integrity point of view.

Local file-system

Imagine the case where the password is stored on the local file-system where the application is running and the application reads the file to obtain the password. The file is stored in plaintext.

- Creation: the user manually writing a file;

- Storage: plaintext file;

- Consumption: the application reads the file.

Security consideration for creation: - The secret is displayed on screen (once more), which will most likely always be the case, and not so much a problem if you are alone in the room.

Security consideration for storage - Secret is stored in plaintext in the file-system. It is quite common for an attacker to find ways to have un-authorised access to a machine’s file-system (far more common then an attacker having access to the environment variables, at least in my experience), which means we are exposing the secret to a bigger risk if compared to the environment variable. I would like to spend a few words to justify why, in my experience, the file-system is an easier target by an attacker. In order for the attacker to compromise the machine, he has to find a vulnerability on a service running on the machine itself. It is quite common for services to provide some sort of reading functionality to access certain parts of the file-system. Such functionalities might be abused by an attacker to access arbitrary location and ultimately the file containing the secret. Little less likely is the case of an application providing explicit functionality for accessing the environment variables that could be abused to access the environment itself. For an attacker to access the environment variables it is more likely he already has some sort of remote command execution capability.

- The storage of the secret is permanent, so a reboot of the machine would not cause the lost of the secret.

Security consideration for feeding: - The application will read the secret from the file-system which makes it safe enough from a confidentiality or integrity point of view.

What about if we want to encrypt the file that contains the password? As we’ve seen before, we end up in the recursive dilemma of the “first secret problem”, where now we are back at square one and should find a way to provide another password to our application.

Database

Imagine the case where your password is stored within a database and your application has to access the database.

This solution is actually not too different from the “local file-system” solution and most of the considerations that we have already explored applies here too, especially if the database is installed on the same machine where the backup application is running.

To make things interesting, let’s consider the case where the database is provided as a service running on a separate machine. For the backup application to access the database, it has to use a network protocol. The network protocol must provide integrity and confidentiality so that an attacker cannot eavesdrop on the network channel, and should also provide authentication, so that only the backup application can access the backup password.

We can consider two solutions for allowing only the backup application to access the database:

- Taking advantage of the network topology so that the machine running the backup application is the only one allowed to access the machine running the database i.e. the backup machine has a physical wired connected to the database machine and the database machine is not physically connected to anything else. This case falls right back into the “local file-system” scenario, the presence of a physical wire that connected the two machines is negligible from a security point of view (remember the assumption on the attacker).

- The machine running the database is located somewhere on the network and the backup application has credentials to access the database. This means that the backup application requires a pair username\password to access the database to retrieve the backup password. This case makes us loop back again in the recursive dilemma of the “first secret problem”: what are we supposed to do with the pair username\password?

Vault

We can think of vaults as an envolved database. A vault is essentially a database that provides helpful functionalities for storing secrets, providing features such as encryption at rest and encryption in transit out of the box along with many others. A vault is also very helpful to developers for lifting the burden of handling secrets.

However, the way they integrate into your application is still very close to what we have seen above with databases:

- A vault is typically running on a separate machine as a service;

- Requires applications to connect to it via some sort of authentication;

- Once authenticated the application get to access secrets.

So here we are again, how to we make the application to authenticate to a vault? We still need to bootstrap security between the two entities.

You might think that there’s another option, since the concept of Vault is often associated with the Cloud, which in turn is often associated with the concept of Identity and Access Management (or IAM for short).

Does IAM solve the first secret problem?

TL;DR: “I’m afraid not Billy”.

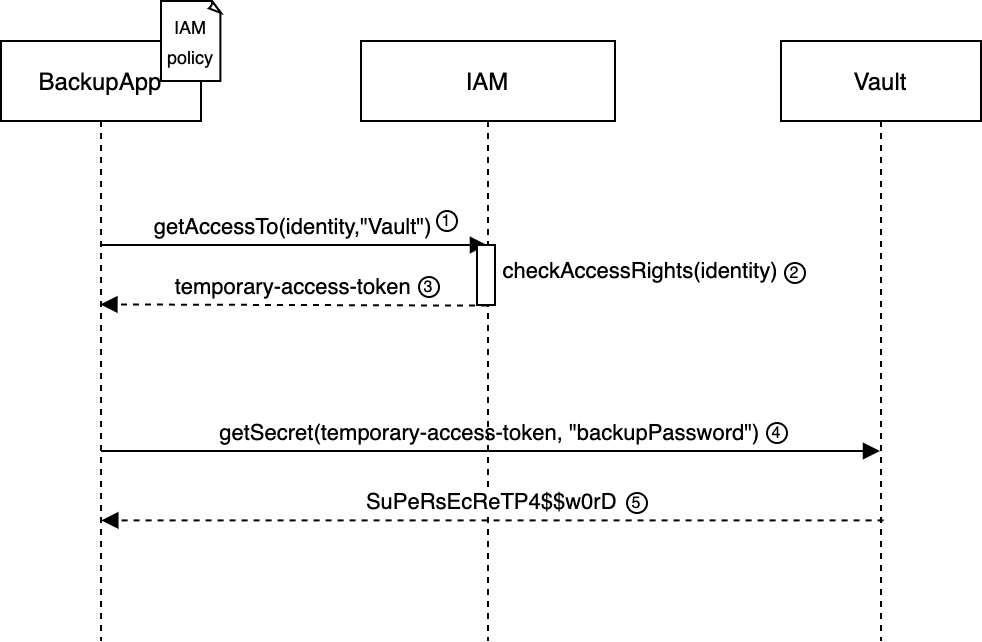

What IAM does is essentially allowing us to specify, given an identity, to which resources or services that identity has access to. The way IAM actually provides access to a resource or service, is still by providing some kind of credentials (typically temporary) so that the identity can access the resource. If we go back to our example, it would work something like this:

The backup application has an IAM policy stating that it can access the vault.

- The backup application requests access for the Vault service to the IAM system;

- The IAM system has the list of policies and identities and checks if the identity making the request has a policy that allows it access to the Vault;

- If the check is positive, the IAM system provides temporary credentials to backup application;

- The backup application can use the temporary credentials to access the vault;

- The vault answers with the backup password for encrypting the backups.

Now the question should be obvious, how do we actually perform step 1-2? How does the BackupApp entity identify itself to the IAM system? This is where, once again, we loop back to the first secret problem.

When you implement the BackupApp entity to access the IAM system you are using a library or SDK provided by the Cloud provider of your choice. The SDK is working some magic under the hood you don’t see, and is retrieving some other secret that can be used to prove its identity to the IAM system.

(The SDK only simplifies access to the credentials which are instantiated, for instance, as environment variables or metadata endpoint and are temporary and rotate frequently.)

What is this? A cat and mouse game?

Indeed it is. As you might have noticed from the brief excursuses of the solutions above, the basic idea behind solving the first secret problem is to put the initial secret far away as possible from the attacker reach, so that we can make the attacker’s life more complicated. As I said at the beginning, there is no one-size-fit-all solution to the “first secret problem” and you have to choose which is the better solution for your case.

To choose the better solution you should use our favourite thing in security: a threat model.

A brief list of things to consider in this case are:

- What kind of attacker you want to protect yourself from,

- What kind of resources are at your disposal,

- The value of the data you want to protect,

- How expensive you solution would be in comparison with the data you are protecting,

- What should definitely not happen,

- What is ok(ish) if it happens.

For example: let’s consider the case above of the backup script that takes a backup of your local NAS and stores it into a network storage in the cloud. In this case you want to encrypt the backup because it’s sent into the cloud and you want to ensure confidentiality, but you might be ok at storing the backup password in plaintext in a cron job because your NAS is running in your local network and does not have a wide attack surface that can be abused by a remote attacker.

On the other hand, if you are running a kubernetes cluster at scale, and have many people working on it, you might want to use a Vault to store secrets since it will provide with:

- a centralised placed so that pods will not have embedded secrets;

- a seamless way for developers to using secrets since the Vault is taking care of the whole lifecycle of the secret itself;

- limited blast radius in case of compromise: if a pod in your kubernetes cluster is compromised, it won’t be able to access all the secrets.

I highly recommend exploring and testing these solutions, try to understand how they work and how they can integrate into your use case.

Stay safe, cheers!