Project Dribble: hacking Wi-Fi with cached JavaScript

I’ve been meaning to work on this little project for quite some time, but life got in the way and I was always too busy. Now I finally got some time back for myself and I’m here talking about it.

Quite some time ago I checked out the Wireless LAN Security Megaprimer course by Vivek Ramachandran (very nice, highly recommended) and incidentally in the same period I was doing some traveling which meant I got to stay in different hotels all providing Wi-Fi. Needless to say, my brain started to go crazy and I’ve thus been thinking about “unconventional” ways to get Wi-Fi passwords.

Can’t turn my brain off, you know.

It’s me.We go into some place,

and all I can do is see the angles.

– Danny Ocean (Ocean’s Twelve)

The idea that I’m about to describe is pretty simple and, probably, not that new either. Nevertheless it was a fun way for me to get my hands dirty and play around with my Raspberry Pi which has been sitting on the shelf for too long.

Description

The idea is to steal Wi-Fi passwords by exploiting web browser’s cache. Since I needed to come up with a name for the project, I first developed it and than named it “Dribble” :-). Dribble creates a fake Wi-Fi access point and waits for clients to connect to it. When clients connect, dribble intercepts every HTTP requests performed to JavaScript pages and injects in the responses a malicious JavaScript code. The headers of the new response are altered too so that the malicious JavaScript code is cached and forced to persist in the browser. When the client disconnects from the fake access point and reconnects back to, say, its home routers, the malicious JavaScript code activates, steals the Wi-Fi password from the router and send it back to the attacker.

Pretty straightforward, right?

In order to achieve this result I had to figure out these three things:

- How to create a fake access point

- How to force people to connect to it

- What should the malicious JavaScript code do to steal passwords from routers

How to create a fake access point

This is pretty simple, it was also covered in the Wireless LAN Security Megaprimer and there are a number of different github repositories and gists that one can use to get started and create a fake access point. I thus won’t go too much into details but for the sake of completeness let’s discuss the one I used. I used hostapd to create the Wi-Fi access point, dnsmasq as a DHCP server and DNS relay server and iptables to create the NAT network. The bash script that follows will create a very simple Wi-Fi access point not protected by any password. I put some comments in the code that I hope will improve readability.

1 | #!/bin/bash |

How to force people to connect to it

DISCLAIMER: I left this section intentionally at a high-level of description without any code for different reasons. However, if it gets enough attention and people are interested about it, I will probably extend it with a more in-depth discussion providing, perhaps, some code and practical guide.

Depending on your target there might be different ways to try and get someone to connect to a fake access point. Let’s discuss two scenarios:

Scenario 1

In this case the target is connected to a password protected Wi-Fi, perhaps the same password protected Wi-Fi the attacker is trying to access. There are a couple of things to try in this case, but first let me discuss something interesting about how Wi-Fi works. The beloved 802.11 standard has many interesting features, one of which I’ve always found … amusing. The 802.11 defines a special packet that, regardless of the encryption, the password, the infrastructure or anything at all, if sent to a client will simply disconnect that client from the access point. If you send it once, the client will disconnect and immediately reconnect, and the end user won’t even notice that something happened. However, if you keep sending it, the client will eventually give up meaning you can actually jamming the Wi-Fi connection and the user will notice that he’s not connected to the access point anymore. By abusing this characteristic, you can simply force a client to disconnect from the legitimate access point it is connected to. At this point two things can be done:

- The attacker can create a fake access point with the same ESSID of the access point the target was connected to, but without a password. In this case the attacker should hope that once the user realizes his not connected to the access point, he would try to manually connect again. The target will thus find two networks with the same ESSID, one will have a locker while the other one won’t. The user might try to connect to the one with the locker first, which won’t work because the attacker it jamming it, and chances are that he might also try the one without the locker … after all it has the same name of the one he wants so badly to connect to … right??

- Another interesting behavior that can be exploited, is that whenever a client is not connected to an access point, it keeps sending beacon packets looking for previously known ESSIDs. If the target had connected to an unprotected access point, and chances are that he did, the attacker can simply create a fake access point with the same ESSID of the unprotected access point visited by the target. As a result, the client will happily connect to the fake access point.

Scenario 2

In this case the target is not connected to any Wi-Fi access point, maybe because the target is a smartphone and the owner is walking on the street. However, chances are, that the Wi-Fi card is still turned on and the device is still looking for known Wi-Fi ESSIDs. Once again, as discussed previously, chances are that the target had connected to an unprotected Wi-Fi access point. Thus the attacker can just create a fake access point with the ESSID of an access point the target had connected to and just like before, the Wi-Fi client will happily connect to the fake access point.

Create and inject the malicious payload

Now comes the “slightly newer” part (at least for me): figure out what the malicious JavaScript code should do to access the router and steal the Wi-Fi password. Remember that the victim will be connected to the fake access point which obviously gives the attacker quite some advantage, but still there are a couple of things to consider.

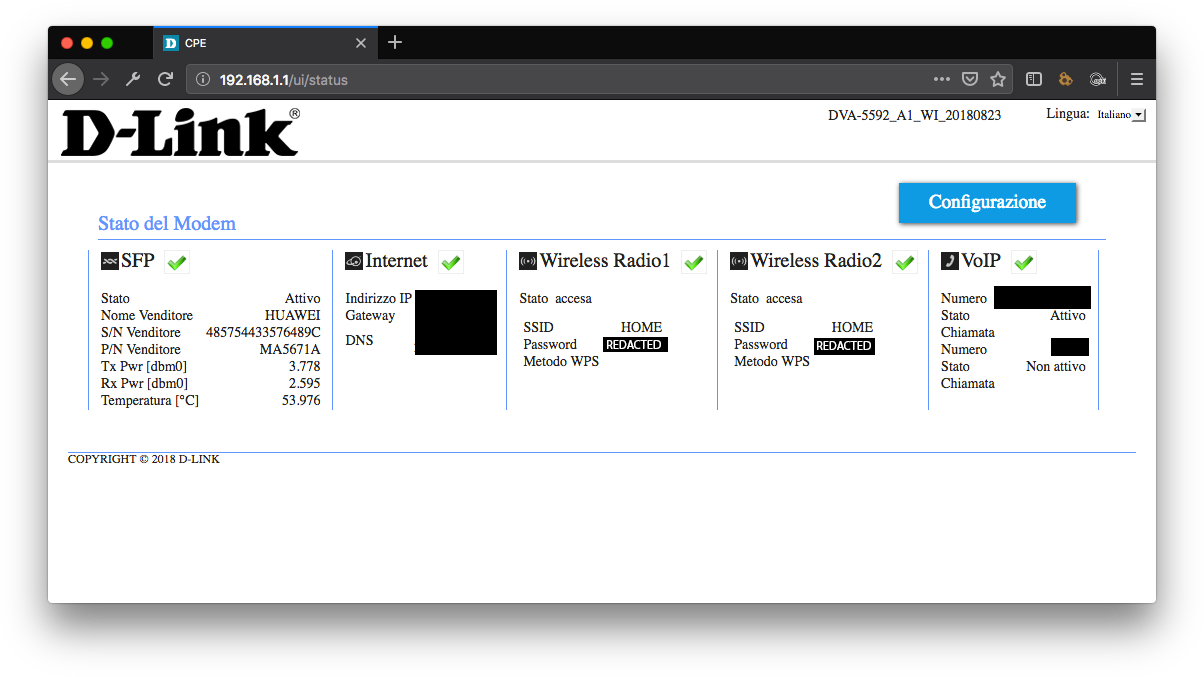

As a target router to attack, I used my home Wi-Fi router, specifically a D-Link DVA-5592 which was (not so) freely provided by my ISP. Unfortunately, for the time being, I don’t have other devices that I can test, so I have to make due with it.

Let’s now discuss the malicious JavaScript code. The goal is to have it performing requests to the router, meaning that it has to perform requests to a local IP address. This should already call for keywords such as Same-Origin-Policy and X-Frame-Option.

Same-Origin-Policy

Let me borrow the definition from MDN web docs:

The same-origin policy is a critical security mechanism that restricts how a document or script loaded from one origin can interact with a resource from another origin. It helps to isolate potentially malicious documents, reducing possible attack vectors. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Security/Same-origin_policy

In other words: if domain A contains JavaScript code, that JavaScript code can only access information within domain A (*). It cannot access information from domain B.

X-Frame-Options

Let me again borrow the definition from MDN web docs:

The X-Frame-Options HTTP response header can be used to indicate whether or not a browser should be allowed to render a page in a

<frame>,<iframe>or<object>. Sites can use this to avoid clickjacking attacks, by ensuring that their content is not embedded into other sites. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Headers/X-Frame-Options

That’s pretty straightforward: the X-Frame-Options is used to prevent pages from being loaded in an iframe.

So let’s see the response that we get from requesting the login page of the D-Link:

1 | HTTP/1.1 200 OK |

The response contains X-Frame-Options set to DENY (thanks god) meaning that if I was hoping to load it in an iframe, I just cannot. Moreover, since the malicious JavaScript code will be injected in a different domain than the one of the router, the Same-Origin-Policy will prevent any interaction with the router itself. The simple solution I came up with, and beware it might not be the only one, is the following:

The injection consists of two different JavaScript code. The first JavaScript code will add an iframe inside the infected page. The src parameter of the iframe will point to the router’s IP address. As already said, the router’s IP address has the X-Frame-Options set to DENY so the iframe won’t be able to load the router’s page. However, when the JavaScript code that creates the iframe executes, the victim is still connected to the fake access point (remember the advantage point I mentioned earlier?). Which means that the request to the router’s IP address will be handled by the fake access point … how convenient. The fake access point can thus intercepts any request performed towards the router’s IP address and respond with a web page that:

- contains a second JavaScript code that will actually perform the requests to the real router,

- doesn’t have the

X-Frame-Optionsheader, - includes headers to cache the page.

Since the fake access point poses as the legitimate router, the browser will cache a page for which the domain is the router’s IP address thus bypassing both the Same-Origin-Policy and the X-Frame-Options. Finally, once the infected client connects back to its home router:

- the first JavaScript code will add an

iframepointing the router’s IP address, - the

iframewill load a cached version of the router’s home page containing the second malicious JavaScript, - the second malicious JavaScript will attack the router.

The first malicious JavaScript is pretty simple, it just has to append an iframe. The second malicious JavaScript is a little bit trickier as it has to perform multiple HTTP requests to brute-force the login, access the page with the Wi-Fi password and send it back to the attacker.

In the case of the D-Link, the login request looks like this:

1 | POST /ui/login HTTP/1.1 |

The important parameters here are:

userNamewhich isadmin(shocking);userPwdwhich looks encrypted;noncewhich is definitely related to the encrypted password.

Diving in the source code of the login page I almost immediately noticed this:

1 | document.form.userPwd.value = CryptoJS.HmacSHA256(document.form.origUserPwd.value, document.form.nonce.value); |

Which means that the login requires the CryptoJS library and takes the nonce from document.form.nonce.value. With this information I can easily create a small JavaScript code that takes an array of usernames and passwords and attempts to brute-force the log in page.

Once inside the router, I need to look around for the location where I can retrieve the Wi-Fi password. The current firmware in the D-Link DVA-5592 shows the Wi-Fi password IN PLAINTEXT (oh boy) right after the login in the dashboard page.

At this point all I need to do is to access the HTML of the page, get the Wi-Fi password and send it somewhere to collect. Let’s now dive into the actual JavaScript code tailored for the D-Link. I included comments so you can follow what’s happening.

1 | // this is CryptoJS, a bit annoying to have it here |

This page should be cached in client’s browser and sent as coming from the router’s IP address. Let’s now put this code aside for a moment and let’s discuss the network configuration that will allow to cache it.

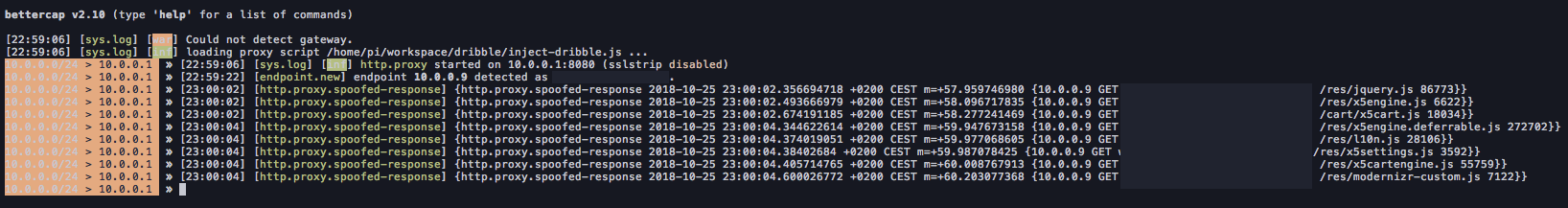

As I just said, the JavaScript code above will be cached as coming from the router’s IP address and will be loaded in an iframe that is created from another JavaScript that I inject in every JavaScript page that the client requestss in HTTP. To accomplish the interception and injection part, I use bettercap. Bettercap allows to create HTTP proxy modules that can be used to program the HTTP proxy and tell it how to behave. For instance it is possible to intercepts responses before they are delivered to the client and decide what to inject, when to inject it and how ti inject. I’ve thus created a simple code, again in JavaScript, that is loaded in bettercap and performs the injection.

1 | // list of common router's IP .. which definitely requires improvement |

One thing is worth noting from the code above, the JavaScript payload tries to load one iframe for every IP in the array routers. This is because the IP of the home router might have been configured differently. This means that the Raspberry has to answer to different IPs on different subnets. To do so, I simply add more IPs to the wireless interface of the Raspberry. In this way, whenever the code that loads the iframe is executed, a request is performed towards common routers’ IP addresses and the wireless interface of the Raspberry can pretend to be the router, answer to those requests and cache whatever I want.

Finally, I need a web server on the Raspberry that listens on the wireless interface and caches the JavaScript code that attacks the router. I did some test with Nginx first, to make sure the idea was working, but finally I opted for Node.JS, mainly because I still hadn’t tried it’s HTTP server (I know).

1 | var http = require("http"); |

Let’s test it out … for real … almost!

At this point I had already done some tests on my own but I wanted to try it in a more realistic environment. However, I can’t just try it on anyone without their consent, so first I needed a victim that would willingly be part of this little experiment … so I asked my girlfriend. The conversation went something like this:

Great, now that I had a victim that willingly decided to participate in this little experiment, it was time to start the hack and lure her iPhone 6 to connect to my fake access point. I thus created a fake access point with an ESSID I knew she has visited before (yes, also intel on your victim can be helpful) and soon enough her iPhone connected to my fake access point.

I let her browse the web while still connected to the fake access point and patiently waited for her to end up on an HTTP only web site.

He waded out into the shallows,

and he waited there three days

and three nights,

till all manner of sea creatures

came acclimated to his presence.

And on the fourth morning, …

Mr. Gibbs (Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl)

Finally, bettercap flickered and printed that something had been injected, which meant I didn’t need to have her connected to my access point anymore.

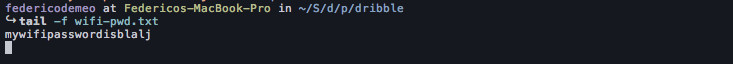

I thus turned off my access point, causing her phone to roam to our home Wi-Fi access point and, since she was still browsing that web site, the malicious JavaScript code that got injected did its job and sent the password of my Wi-Fi network straight to my PHP page.

Wrapping up

The whole thing is available in my github, it can definetly be improved and, hopefully, by the time you read this it already has. Support for new routers should also be added as well. If I have the change to put my hands on other devices I will definetly add them to the repository. In the meantime, have fun and …